Setting Sail in a Small Boat

“Time isn’t just one thing,” says Kyozo Shimogawa, his speech peppered with a Kyushu accent. Though he speaks with a gentle smile, as the conversation unfolds, a glimpse of a boyish dreamer—or perhaps a quietly ambitious visionary—begins to appear. In recent years, Shimogawa has received international acclaim for showcasing his textiles at leading venues like Premiere Vision and the Cannes Film Festival.

Shimogawa Orimono is located on the flatlands near the Yabe River, which flows into the Ariake Sea. The workshop was founded here after World War II and now employs about ten craftspeople. Several small, single-story buildings dot the premises, and in the courtyard, bundles of indigo-dyed Kasuri threads hang from bamboo rods to dry. Inside, the rhythmic clang of weaving machines echoes through the factory. Sunlight pours through skylights, making the freshly woven Kasuri even more striking.

Shimogawa’s business revolves around three core elements: the workshop as a production base, the Kasuri fabric it produces, and the creative networks it fosters. As an entrepreneur with a visionary streak, he explains his business philosophy like this:

“If I were to compare a company to a ship, large ships are hard to launch but can carry many people and things with stability. But we’re not like that. We want to have lots of small boats, spreading out like a spiderweb, making connections as we go out into wider waters.”

The Kasuri woven through many meticulous steps at the workshop is loaded onto Shimogawa’s “small boats” and passed directly to those he connects with. It’s this kind of business that creators around the world are now seeking.

Encounter with Young Designer Hana Mitsui

Shimogawa’s connections abroad grew as he began collaborating with people who possessed talents different from his own. “I can intuitively create fabric from a single thread,” he says. “But I can’t envision how to turn that fabric into a product. That’s where artists and designers come in.”

One such designer is textile artist Hana Mitsui. Although we couldn’t meet her in person for this article, we later had the chance to interview her separately. After graduating from an art university in Tokyo, Mitsui pursued graduate studies in London. Hoping to work closely with textile production regions, she joined ISSEI MIYAKE and later launched her own textile studio after going independent. Early in her solo career, she became involved in product development for the luxury brand LOEWE and that’s when she met Shimogawa.

Kurume Kasuri usually requires large production lots, which makes it difficult for individual designers to work with. However, around that time, Mitsui encountered Takahiro Shiramizu, founder of Unagi no Nedoko, and a collaboration was born. This led her to a deeper understanding of Kasuri’s techniques and processes.

She continued to attract opportunity. Just as she was ready to begin her independent activities in earnest, she secured a spot in “SaloneSatellite,” a gateway for young designers. Having already built trust with Shimogawa through projects with LOEWE and Unagi no Nedoko, she found him supportive. “He told me, ‘The results will follow—let’s just go for it!’” she recalls. Together, they embraced new challenges.

“What I find most fascinating about working with production regions is the discoveries you make in the process,” says Mitsui. “Even if you think things through in your head, once you actually do the work, you find things that can only be learned through handcraft or on-site experience. Craftspeople have accumulated so many insights over the years. I’ve found the results can be more interesting than I imagined.”

They began developing a textile based on the visual illusions characteristic of Kurume Kasuri for her SaloneSatellite presentation. The final piece stood out at the event, which gathers creatives from all over the world, and sparked widespread interest in the appeal of Kurume Kasuri.

The Behind-the-Scenes Role That Keeps on Fascinating

Why did Shimokawa start collaborating with artists and designers in the first place? When asked, he responds:

“Everyone tries to sell where there’s already a track record—department stores, exhibitions, that kind of thing. And that’s fine. But I think you also need to create your own path. Once a road is established, it gets congested. You need to build traffic lights. If that’s the case, why not make a different road? I’m not saying you can only go one way—having multiple routes is a strength.”

An unexpected source of inspiration for Shimokawa was the Japanese entertainment industry. While trends come and go quickly on television, he noticed that behind the scenes, certain individuals remain constant. These behind-the-scenes producers—who never take the stage—shape everything. Take Yasushi Akimoto, for instance: he produced both Onyanko Club and AKB48. That got Shimokawa thinking—maybe it’s more interesting to have different artists and designers use his fabrics each year.

“I want people to come looking for me—someone who says, ‘I want to meet that Shimogawa craftsman and make something with him.’ I think it’d be great if I became almost like an urban legend.”

下川さんのインスタグラムより @shimogawakyozo

With that vision, Shimogawa began sharing information on social media aimed at artists and designers. This started over ten years ago. Slowly but steadily, his network of creative collaborators has grown.

Connecting with the Past

Let’s return to his opening remark: “Time isn’t just one thing.” After forming relationships with overseas creators and frequently traveling to France and Italy, Shimogawa began contemplating the concept of time more deeply.

“We assume time flows linearly from past to present to future, but lately I’ve been questioning that. When you travel to the other side of the world, you go ‘back in time’ compared to Japan’s timeline. There may be other ways of moving through time, too. When making things, I think it’s important to consider what time really means.”

Whenever Shimogawa reflects on time, one figure always comes to mind: Den Inoue, the originator of Kurume Kasuri. She never hoarded her knowledge but taught it throughout her life to the farmers in the Kurume domain.

“I guess I’m one of Den’s disciples, in a roundabout way. If that’s the case, then I should do what she did. I want to teach people overseas with the same mindset. There was a time I thought I was doing something groundbreaking, but now I realize that in the grand scheme of history, I wasn’t doing anything new—or wrong.”

Working with this philosophy, Shimogawa finds himself able to vividly imagine life 100 or 200 years ago.

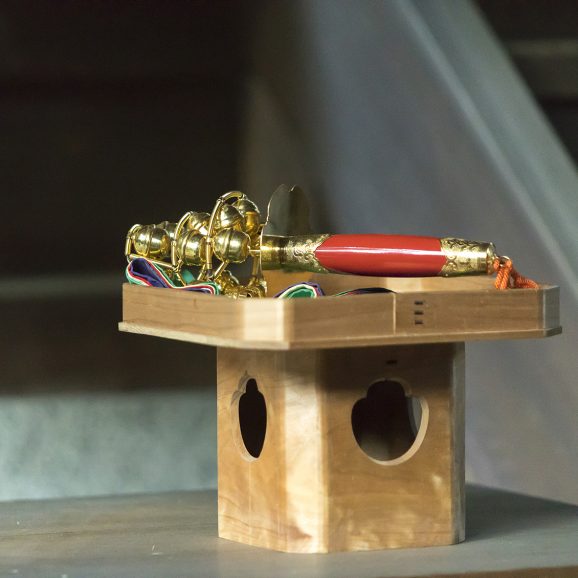

“When I touch old tools or objects, I feel the energy of the era buzzing through me, like in a detective drama. Even when I handle a single thread, I see colors and patterns emerging from it.”

He sees how people of the past might have experimented with tools and materials. These reflections guide his decisions—not based on external factors like the market or modern time structures, but from an internal compass shaped by the visions of his predecessors. He’s fascinated by how such an approach might be evaluated on the world stage.

“Thinking is one of the greatest abilities given to humans. Imagination can transcend time. We didn’t always have clocks or airplanes—but the day came when they became commonplace.”

The Value of the Ordinary

Shimogawa lives a highly regimented life. “I think I’m more disciplined than an elementary school student,” he laughs. He wakes, eats, works, and sleeps at set times every day.

“I don’t like disrupting this rhythm. By creating an orderly and ordinary routine, I’m exploring how to bring the extraordinary out of the everyday. I think it’s fascinating when an unassuming craftsperson, living quietly in rural Japan, can create something special from within that normalcy.”

From his collaborations with artists and designers, to his deep awareness of time, to his embrace of the ordinary—Shimokawa’s unique approach to making may lead Kurume Kasuri into new and unexpected forms. In doing so, it might even reveal unseen possibilities for the future of craft itself.

※The English text of this article is an automatic translation generated by AI.

SPECIAL

TEXT BY Kiiko Nakai

PHOTOGRAPHS BY Nozomi Moritani

25.04.23 WED 15:49