Kyushu Craftsmanship, Hidden Throughout the Inn

Craft Inn [té], the stage for today’s story, stands among a row of stately, white-walled merchant houses in Fukushima District, Yame City. Created as “an inn to experience the craftsmanship of Kyushu,” it invites guests to engage with local traditions like bamboo crafts, indigo dyeing, and washi papermaking. The two-story building has a wide, sturdy facade, with striking reddish wooden window frames. Hanging by the entrance is a distinctive lantern crafted by Gen Taniguchi, a master of handmade Nao washi paper, instantly drawing your gaze.

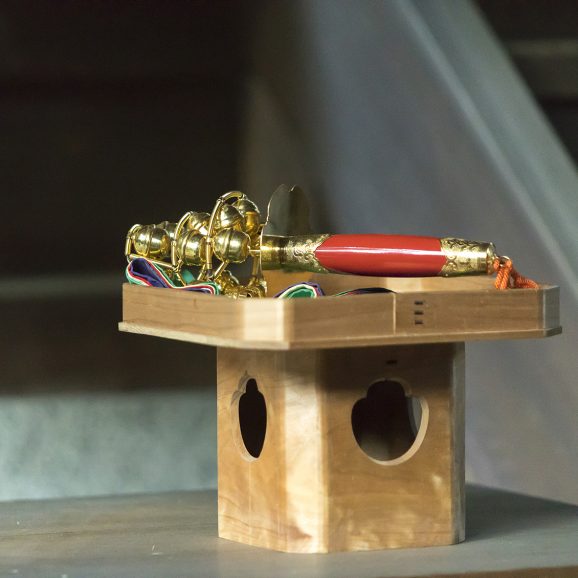

Stepping through the white noren curtain, you’re greeted by a charming stone round table made from local materials—an invitation to sit down naturally. Beside it stretches a shelf lined with finely crafted objects from the surrounding region.

By this point, guests have already begun experiencing Kyushu’s craftsmanship not just with their eyes and hands, but even their bodies. Upstairs, in one of the guest rooms, Aya Tamura, co-representative of UNA Laboratories, the company behind Craft Inn [té], welcomed us. In the quiet, late afternoon town of Yame, she spoke thoughtfully. Though she lives in Fukuoka City, Aya commutes here by train and bus—a one-and-a-half-hour journey each way. That rhythm of coming and going seems to shape her sensitive, grounded way of engaging with the place.

The Weight and Lightness of Running an Inn

Originally from Kanagawa Prefecture, Aya worked at an advertising agency in Tokyo before transferring to Fukuoka. In 2019, she co-founded UNA Laboratories (UNA Lab) and began commuting to Yame, bridging city and countryside.

UNA Lab runs not just Craft Inn [té] but also a travel agency and various projects commissioned by local governments. They first started with travel services, but launching the inn enabled them to offer craft-focused tours where guests visit and experience local artisans’ studios firsthand. The Yame region, once a thriving merchant area blessed with rich natural resources, is home to a wide variety of crafts: Kurume kasuri textiles, Buddhist altars, lanterns, washi paper, woodworking, bamboo crafts, ceramics, sake, Yame tea, and more.

Starting a lodging business in a craft region like this carries its own meaning. In a previous interview, Aya mentioned feeling that “people who inherit family businesses carry a different weight on their shoulders.” We asked if her perspective had shifted since then. She responded:

“Of course, we bear responsibilities as business operators. But I still feel the burden is different compared to those inheriting a family trade across generations. Maybe because of that lightness, we can do things differently—and that’s precisely our responsibility.

Still, ever since we started the inn, I feel a deeper sense of being rooted here. Lodging isn’t something you can manage just from behind a computer screen. Every day brings small, tangible issues that must be handled. Facing those challenges makes me feel more truly connected to the community.”

Those daily challenges include repairing rattling windows, cleaning up after wild animals, preparing for typhoons, weeding, and countless small interactions with neighbors. Through this kind of hands-on, detailed stewardship, Aya and her team explore how to build a meaningful relationship between themselves and this deeply historical, localized place.

She adds, with careful nuance:

“Looking at the big picture, yes, many things are disappearing. But even if we don’t do it the same way as people with longstanding family businesses, maybe there are still things we can contribute.”

By sharing, preserving, and nurturing, they aim to pass these traditions onto future generations—and Craft Inn [té] stands as a living platform for that work.

Working as We

Midway through our conversation, one thing stood out: all of UNA Lab’s core operational members happen to be women.

In our previous article (vol.1), we interviewed Takahiro Shiromizu, a visionary who casts his words far into the future. In contrast, Aya carefully builds language starting from “here,” grounding every idea in the daily realities of operations and services. Alongside such leadership, a lively team of women—mostly in their 40s—form the heart of UNA Lab.

What surprised us was this:

“Everyone is multitasking. Our full-time staff handle travel bookings, project management, guiding tours, and even housekeeping.

Even the lodging-focused staff manage the front desk, clean rooms, serve breakfast—you name it.”

As a small company, UNA Lab cannot afford the kind of specialization larger corporations can. Plus, many members are raising children, so being able to flexibly cover multiple roles is essential.

At the same time, they are deeply, sharply focused on an important internal question:

“What do we want to do? What can we do?”

Aya continues:

“Some travel agencies provide 24/7 concierge service, but that’s not realistic for us.

Instead, we think carefully about what kind of breakfast, what kind of space truly feels right—through a ‘native’ lens, grounded in our values.”

What connects the team is their shared commitment to respectfully preserving and passing on the cultural heritage of their region. Their mission isn’t just about “distributing” local culture—it’s about fostering it, slowly, from the ground up.

“Now that we’re entering our sixth year, I really feel we’ve built a good team.

Even without putting everything into words, I think what matters is being passed along naturally.

These days, instead of having a dedicated inn manager, I personally come regularly to clean, adjust operations with the staff, and chat with locals.

Honestly, I think that’s the way it’s meant to be.”

The resulting space, lovingly maintained down to the smallest detail, feels effortless and deeply comfortable. Even the tableware and linens seem to quietly express the team’s gentle but wholehearted devotion.

New Local Cultures, Born Here and Now

Aya reflects that she also enjoyed her previous career in Tokyo’s fast-paced advertising world.

Yet what she finds profoundly compelling about her current work is:

“In these communities, you’re creating things alongside people who are truly making things with their own hands.

There’s a vividness—a raw, tangible sense of creation—that’s incredibly exciting.”

When asked about memorable moments in her work in Yame, she mentioned the collaboration with an indigo-dyed kasuri weaving studio whose tapestries now adorn Craft Inn [té].

“In Japan, they say there are 48 shades of indigo.

We asked a local craftsperson to dye fabrics in all 48 shades—but they came back with 100 colors!

They said, ‘I just kept going!’

It was amazing to experience something being created so spontaneously, so live and vibrant.”

Places labeled as “traditional craft regions” often get boxed into fixed images. But as the indigo story shows, real creative sites are dynamic—constantly changing, improvising, and flowing.

“Regional culture, to me, is something that has always been continuously optimized to fit the local needs at any given time.

I want to present ways of interpreting that dynamism.”

Another unforgettable episode involved a project hosted by Fukuoka Prefecture, where graduate students from Parsons School of Design in New York came to Yame to work with Kurume kasuri weavers.

Originally, the plan was for students to weave existing designs during a short stay. But a question arose:

Would that really contribute meaningfully to the craft community?

In response, UNA Lab suggested extending the students’ stays and allowing them to design their own patterns.

As a result, entirely new, unexpected creations were born.

“Especially in our travel projects, we want to avoid reducing local culture to just a commodity exchanged for money and services.

Ideally, the artisans themselves feel stimulated and inspired—and new creation is sparked.”

By engaging with artisans in a genuinely open and collaborative spirit, new life and new stories continue to emerge from the region.

Through it all, Aya and her team never lose sight of why they do what they do, constantly adjusting their course, constantly re-asking the important questions.

“For me, ‘native’ isn’t about geography—it’s a way of seeing and engaging with the world.

There are natives in Tokyo, in New York, everywhere.

We happen to find Yame particularly fascinating right now, but it’s not that Yame is inherently superior.

I want to face local culture with that open, expansive mindset.”

And today, as always, Aya continues moving between city and countryside, reflecting steadily on what she can offer, here and now.

※The English text of this article is an automatic translation generated by AI.

SPECIAL

TEXT BY Kiiko Nakai

PHOTOGRAPHS BY Nozomi Moritani

25.04.23 WED 15:49