Economizing Craftsmanship

9 a.m. in the quiet streets of Yame, before the shops open.

We meet Takahiro Shiramizu, founder of “Unagi no Nedoko”, standing casually in his signature “monpe” work pants, exuding a quiet ease. We walk together to his office, and the interview begins. Light-hearted banter gradually gives way to a focused conversation.

“I don’t have a personal attachment to craft. It’s fine if it disappears or not. It’s better if it stays, sure—but if it goes, that’s just how it is.”

This offhand remark kicks off our talk. At first glance, it feels cold, but as the conversation deepens, the meaning behind his words becomes clearer. Our discussion spans local engagement, the methods built upon it, and his own career path—revealing the thoughtful gaze of someone who has led Unagi no Nedoko for 12 years.

Speaking with Shiramizu in the shipping area of “Unagi no Nedoko”.

Founded in 2012 in Yame, Fukuoka Prefecture, “Unagi no Nedoko” started as a local culture trading company and antenna shop. When I visited years ago, I was struck by the volume and variety of products—far more than a typical select shop. Most striking were the QR codes beside each item. Scanning them led to richly detailed profiles of each maker, often around 400 characters—about a full page in Japanese manuscript format—explaining their techniques, history, and recent innovations. It felt like teleporting directly to the maker’s world. I’ve never been so drawn into store shelves before.

Shiramizu, originally from Saga Prefecture, studied architecture at Oita University before working on employment creation programs for Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Fukuoka. At 27, he founded “Unagi no Nedoko”. At that time, few shops focused on usable, everyday craft or supported local creators’ self-expression. Within a few years, the company grew to 7–8 people. With the opening of the Terasaki House in 2017, staff increased to 15. By 2020, with new locations in Lalaport Fukuoka and Acros Fukuoka, the team expanded to over 30. Today, around 40 people work in operations, sales, sourcing, logistics, photography, design, and even product planning and production. The company internalized a wide range of functions. During the pandemic, more makers began to share their stories, and interest in crafts shifted. Shiramizu reflected, “Middlemen like us must evolve quickly to match reality. ” This awareness of shifting roles—both personal and industrial—led him to hand over the company’s management to another in March 2024.

Seeing Craft Like a Doctor: A Preventive Approach

I told Shiramizu that I perceived the sheer volume of goods and information in the store as a kind of “heat”—a palpable energy. That’s when he responded with his earlier “no attachment” remark, followed by this: “Many in my family are pharmacists. My father is a doctor who practices Eastern medicine, particularly Chinese herbal therapy. He emphasized preventive medicine over reactive treatment.”

Doctors don’t necessarily treat patients because they’re emotionally attached—they act because something must be done before things get worse. Similarly, his involvement in local craftsmanship is not driven by sentiment, but by a sense of proactive necessity. “In the Netherlands, for example, art, design, and agri-tech are big, but that’s because traditional craft completely vanished. A shop owner there told me, ‘Japan’s lucky—your government still supports craft, and department stores still carry it.’ It’s true. Once it’s gone, people regret it. So even preserving it in small ways is worth the effort.”

The townscape of Yame, lined with tea shops, fireworks stores, and traditional fish cake makers.

This pragmatic stance reveals his philosophy. “In regions like ours, you often get people with intense emotional investment. But if everyone is like that, it won’t work. You need people who can approach complex systems dispassionately. That’s been my role.”

In local communities, those involved often find themselves tested for their “authenticity,” carrying emotional burdens. But Shirouzu’s steady, objective approach seems essential to long-term commitment. It’s this attitude that’s brought Unagi no Nedoko to where it is now.

His methods also echo medical thinking. When building new movements in an industry, he identifies the problems first: “What’s weak in this industry? Then let’s build a framework now to prevent future issues.” Or, in the case of towns:

“If we create this business in this specific place, we can support local craft and prevent closures.”

It’s about building healthy conditions—not reacting from the market backwards, but starting from the current state, analyzing it like a doctor does a patient, and planning accordingly. For him, if medicine heals the body, business builds the region. If herbs are a physician’s tool, then enterprise is his.

Not Just Selling Things: Economizing Craft

What does it mean to create “preventive” business models? Shiramizu says it’s about being “database-oriented.” His team maintains a network of local makers, food producers, and public offices, drawing from it based on the needs of each visitor. “There’s no message from the store itself.” When seen as a database, the overwhelming product variety makes sense. A ¥1,500 mass-produced cup and a ¥5,000 artisan cup may sit side-by-side—targeting different buyers, but both embedded in local context. This deliberate curation lets customers discover unexpected value. “People only see the world through their own perspective. So I think about how to build a database that allows for multiple interpretations.”

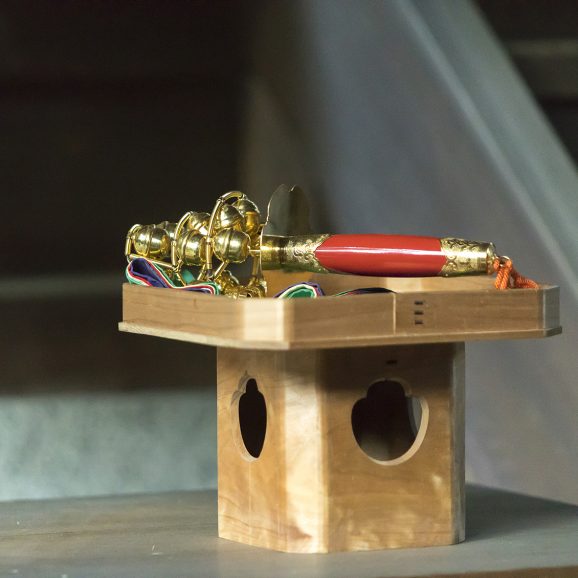

“Inside “Unagi no Nedoko” former Terasaki Residence: the first floor is filled with tableware, processed foods, and toys, while the second floor features apparel and everyday items like detergent—all densely arranged within a traditional townhouse setting.”

And the database’s output isn’t limited to retail—it could be tourism, lodging, or original products appearing throughout Yame.

Take tourism. Many Western visitors value Japanese “craftsmanship,” but not necessarily the “products.” What resonates is the fact that these crafts have been passed down and still exist. But in Kyushu, with its flexible “yoka yoka” culture (“it’s all good”), craft workshops have long offered factory tours for free. The value that foreigners feel? It’s been monetized at zero yen.

So, by packaging these tours into products based on his database, Shiramizu sees a way to make craft economically viable beyond just selling goods.

“Until now, we’ve tried to sustain craft by selling things. But I don’t think that’s enough anymore. Recently, a textile specialist from the U.S. joined a tour and spent a lot in the region. That kind of economic activity didn’t exist in our previous supply chains. We need to enhance the value of what we sell, and realize the hidden value outside of that system.”

Shifting Paths

Now a senior advisor after handing off the company, Shiramizu speaks about “shifting”—a concept that defines his outlook.“ I come from a medical family, and though my field changed, that mindset stayed with me. I think it’s vital to intentionally shift people from their area of expertise into new contexts. Once someone is displaced, they adapt and thrive on their own.”Medicine turned into architecture. Architecture turned into local business. These were all shifts. “How to create that first shift—that’s my eternal theme.” Toward the end of the interview, Shirouzu said: “All that matters is: what’s really happening?”

His focus remains on actual conditions—of the body, buildings, or towns. After over a decade in traditional crafts, he senses a growing movement: people driven by urgency, trying to understand fundamental systems and change how things are done. When their time comes, perhaps craft itself will shift toward a new world.

In front of Unagi no Nedoko’s former Terasaki Residence.

Takahiro Shiramizu

Founder and Advisor, Unagi no Nedoko

Born in Saga Prefecture in 1985, Takahiro Shirouzu graduated from the Faculty of Engineering at Oita University. He began his career as the chief coordinator for the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s regional revitalization project, “Kyushu Chikugo Genki Keikaku.” In 2012, he founded Unagi no Nedoko as an antenna shop representing the Chikugo region of Kyushu. As a regional culture trading company, Unagi no Nedoko introduces products from around 250 makers, primarily in Kyushu but also from across Japan. In 2015, Shirouzu developed and commercialized MONPE pants using Kurume Kasuri fabric and has since collaborated with textile-producing regions nationwide.

After managing the company for 12 years, he entered a capital partnership with Takeover Inc. in March 2024 and now serves as founder and advisor. He also established Shiramizu Inc., aiming to explore multiple new ventures. The Kyushu Chikugo Genki Keikaku project received the Good Design Award’s Chairman’s Prize from the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

※The English text of this article is an automatic translation generated by AI.

SPECIAL

TEXT BY Kiiko Nakai

PHOTOGRAPHS BY Nozomi Moritani

25.04.23 WED 15:46